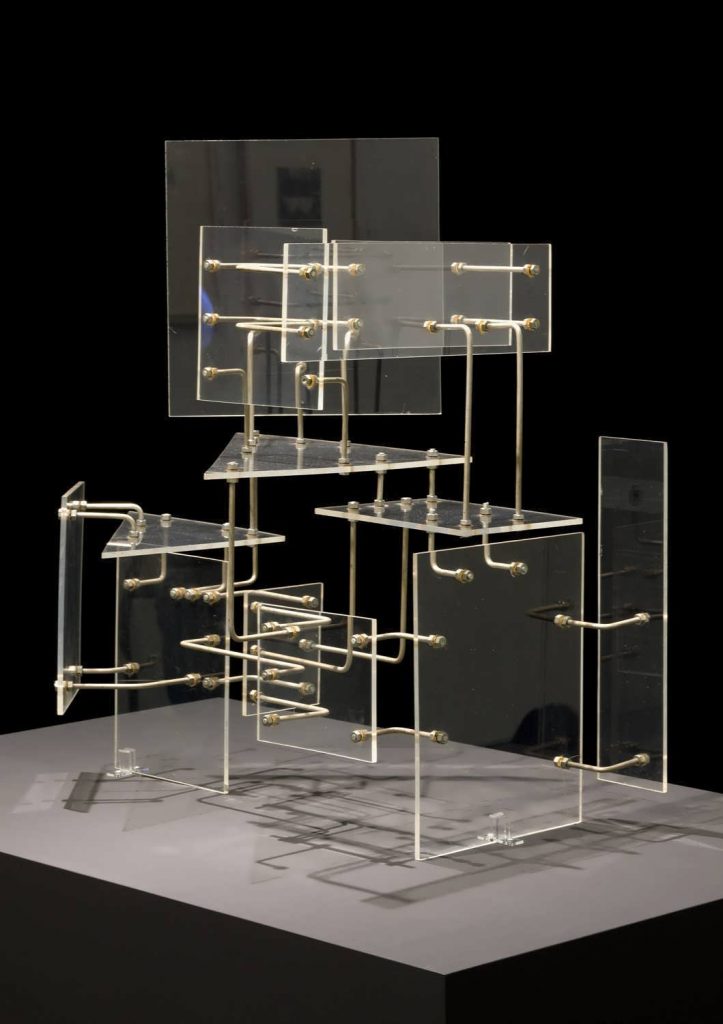

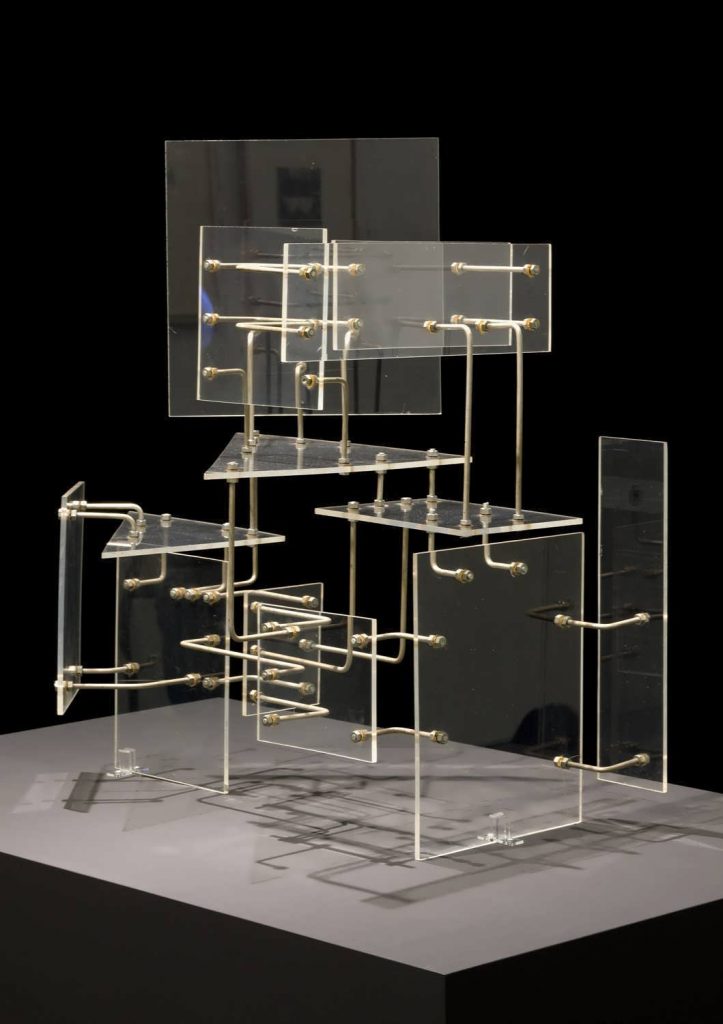

Construction aux plans transparents

Constant

Obra

Autor

Constant

Any

1954

Tècnica

Metacrilato, aluminio y hierro

Any d'adquisició

2009

Estado

En exposición

Tipo de objeto

Escultura

Dimensiones

76 x 73 x 48 cm (alto x ancho x fondo)

Crédito

Colección MACBA

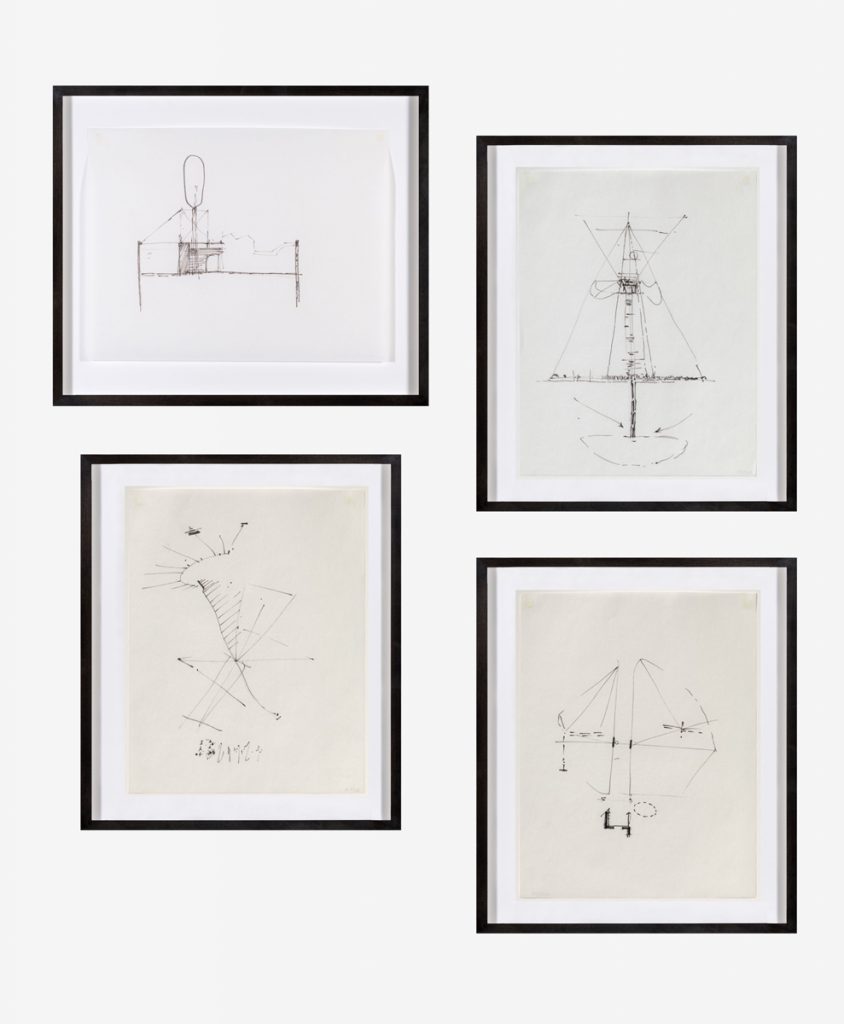

In 1956 Constant began to work on New Babylon, a visionary architectural proposal for a future society. Aker World War II, when throughout Europe cities damaged during the war were being rebuilt, Constant turned to developing a series of prototypes for a utopian city. Abandoning painting, he focused on developing a situationist city. Constant maintained that the rational, monotonous functionalism then being utilised would limit a free and creative life. He thus began designing architectural structures for the future. This was New Babylon, elaborated in an endless series of extremely detailed models, sketches, etchings, watercolours, lithographs, topological maps, collages, architectural drawings and photo-collages, as well as in manifestos, essays, lectures and films. ‘What is New Babylon actually?’ Constant wrote in 1966. ‘Is it a social utopia? An urban architectural design? An artistic vision? A cultural revolution? A technical conquest? A solution to the practical problems of the industrial age?’ Constant maintained that New Babylon dealt with all of these questions, envisaging a society in which traditional architecture has disintegrated along with the social institutions that it propped up. Every reason for aggressivity had been eliminated in New Babylon, making place for a society of creative people who are freed from stultifying everyday work, for a new species: Homo Ludens(man the player).

New Babylon is a nomadic world, a labyrinth-like city in constant transformation. A vast network of enormous multilevel interior spaces would propagate to eventually cover the planet. These connecting pieces, called sectors, would have multiple stories with transparent floors and hover above the ground on tall columns of varying design. While vehicles rushed underneath and air traffic landed on the roof, the inhabitants dispersed by foot through the huge labyrinthine interiors, endlessly reconstructing spaces and atmospheres.

Every aspect of the environment could be controlled and reconfigured spontaneously. This was to be the ludic city where the New Babylonians would be free to create and recreate the city as they wished. By the early 1970s, Constant had come to recognise that leaving the liberated id to its own devices wouldn’t lead to paradise. Two decades after embarking on his vision of a city given over to the pleasure principle, he realised the dark side of the id unbound. Before abandoning the project, in his final series of drawings he sketches an apocalypse in black and red: madness, slavery, dehumanisation, the dystopian consequences of unquenchable desire.

Though Constant positioned New Babylon at the threshold of the end of art and architecture, it has had a major influence on the work of subsequent generations of architects, provoking intense debates at schools of architecture and fine arts about the future role of the architect. It prefigures projects by Frank O. Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Philippe Starck, Nigel Coates, Greg Lynn and other architects who have imbued individual buildings with the rich emotional impact of urban experience. His project even looked further into the future, toward the cyber spatial network that now encircles the globe.